Solidarity and Intergenerational Equity

The sixth Scotia Group dialogue

If we want an historical precedent that proves it is possible for governments to effect dramatic improvements on a continental scale, we have only to think of George C Marshall’s State Department, and its formulation and implementation of the European Recovery Program.

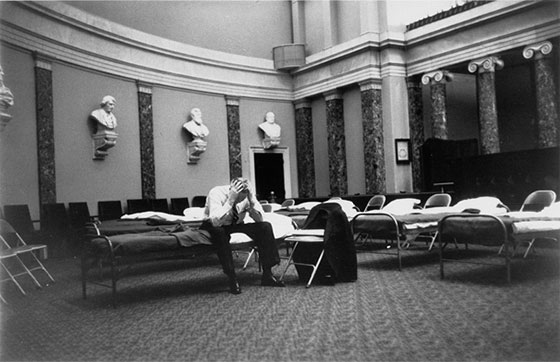

January 1947 is still part of British historical memory. This was the month that turbines stopped spinning, the radio went off the air, offices and factories closed. The picture was worse in much of mainland. In Berlin, 150 people froze or starved in the city’s ruins; in undamaged Copenhagen, they fought over coal. There were many cities across Germany, Poland and the Soviet Union in which hardly a building was left standing. In Italy, everyday experience was, for many, little more than a primitive struggle for survival.

Monetary systems were breaking down, and everywhere, there were shortages of the capital, machinery and infrastructure needed to restart economic life.

Builders in West Berlin working on a project funded with Marshall Aid in 1952 | License link

The effect of the Marshall Plan is also part of European historical memory.

The transfer of $13bn of food, fuel, investment and industrial assets is the starting point of contemporary Europe, with its Wirtschaftswunder and Trente Glorieuses.

The cost of the Marshall Plan is around $120bn in 2021 dollars – a sum that seems strangely small when set beside the trillions that are being talked about in Washington and Brussels’ as politicians and planners contemplate our own generation’s disaster recovery programmes. What it showed, in the most dramatic way possible, was that the strategic application of resources can cause wide ranging positive change in the real world.

The Marshall Plan Stamp | License link

“The world situation is very serious”

This was the point made by Malik Dahlan, the founder of the Scotia Group, in his opening address to the sixth dialogue. This meeting was hosted by the University of Harvard’s Weatherhead Center for International Affairs on 21 September, and met under the heading of “Solidarity and Intergenerational Equity”. The choice of location and historical parallel was apt, because General Marshall outlined his plan in a speech to the same university in June 1947, and what he had to say to the alumni then seems just as applicable to our present emergency.

The Marshall Plan speech at Harvard University, June 1947

“I need not tell you, gentlemen, that the world situation is very serious. That must be apparent to all intelligent people.

I think one difficulty is that the problem is one of such enormous complexity that the very mass of facts presented to the public by press and radio make it exceedingly difficult for the man in the street to reach a clear appraisement of the situation.

Furthermore, the people of this country are distant from the troubled areas of the earth and it is hard for them to comprehend the plight and consequent reactions of the long-suffering peoples, and the effect of those reactions on their governments in connection with our efforts to promote peace in the world.”

General Marshall arrives at Harvard to make his speech | © George C Marshall Foundation

As Professor Dahlan put it: “The world grew to believe that any grand US foreign policy was possible, no matter how lofty.

What is needed today is a Marshall Plan for climate.

The UNFCCC Synthesis Report, published last Friday, covered the national determined contributions (NDCs) agreed in Paris six years ago. It showed that the contributions of all 191 parties, taken together, imply an increases in greenhouse gas emissions of about 16% in 2030 compared with 2010.

So, we’re moving backwards. Such an increase will lead to a temp rise of about 2.7°C by the end of century.”

This latest finding prompted the Scotia Group to issue a Statement of Diplomatic Emergency to António Guterres, the UN secretary-general. It called for a continuous international effort to agree concrete plans for action in the immediate future. This could be taken as a rallying cry for Western liberal democracies, but “what was interesting was that our statement gained ground in China, where the message cut through that it and the US needed to work together to formulate a global policy of decarbonisation and commit to energy transition diplomacy”.

A decade after the plan, Europe was experiencing continuous economic growth – with no sense of what the costs might be | Stahlkocher, CC BY-SA 3.0

What are we going to do?

If the Marshall Plan created a world safe for Boomers to romp and prosper, what are we going to do to protect the life chances of generation Alpha – the first cohort of which is now approaching its ninth birthday?

That was the burden of the sixth dialogue, and to address it the Scotia Group made some changes to the usual agenda.

Firstly, our speakers were drawn from students and recent graduates from Harvard, all of whom have taken on aspects of the climate challenge in their studies and professional lives.

Secondly, the sociable, off-the-record majlis that usually occupies the second hour of the dialogue was replace by presentations from four teams of Scotia Group Fellows. These are young people drawn from our partnering universities who have been auditing the discussions so far, and have come up with specific policy proposals to put to the decision-makers at COP26, and possibly those at COP27 as well. These proposals were then assessed by a jury of Scotia experts, and the winner was awarded the inaugural Stanley Hoffman–Louise Richardson prize, which offers £25,000 to an innovative policy proposals from someone under the age of 35.

The first session was moderated by two professors from Harvard’s Department of Government: Melani Cammett and Dustin Tingley. Melani is the director of the Weatherhead Center, and as her biography shows, her research interests are a perfect fit for the concerns of this dialogue.

Melani Cammett

Melani is the Clarence Dillon Professor of International Affairs and holds a secondary faculty appointment at the TH Chan School of Public Health. Her research explores toleration after ethnoreligious conflict, identity politics and the politics of economic and social development. She has published four books, numerous articles in academic and policy journals, most recently “Building Solidarity: Challenges, Options and Implications for Covid-19 Responses”.

Melani began by making the point that climate change, like Covid-19, is an existential threat to every human on Planet Earth. And, like the virus, it is as much a political as a technical problem, in as much as it will require people around the world to gather round tables in both kitchens and conference rooms. And it may be that more gets done at the former than the latter, since

“we know from research on collective action that it’s easier to construct solidarity in communities that feel a sense of we-ness”

Our co-moderator, Dustin Tingley, was an equally appropriate choice. He has specialised in, among other things, improving the teaching/learning process – and education will certainly be important in presenting students of all ages with the “mass of facts” about what environmental degradation means, as well as the tools to untangle their “enormous complexity”.

Dustin Tingley

As well as his professorship, Dustin is the deputy vice provost for advances in learning, faculty director of Harvard’s Higher Education Data Science Group, and faculty director of the Harvard Initiative on Learning and Teaching. His research interests include international relations, international political economy, data science, and he’s begun an initiative at the university to promote research into climate change.

As his biography suggests, Dustin has done much to put climate action on the agenda at Harvard, and thereby bring it to the attention of America’s future opinion formers and decision makers. A start has already been made by the creation of an environmental science & public policy major, and the political science department will be offering its first lecture course dedicated to the topic this spring. A greater challenge, perhaps, is finding openings in the American jobs market for the green graduates that will be produced by these courses – a subject that was taken up by our speakers.

GENERATION GAP REDUX

Aleksandra’s talk was about what the opinion poll and social media data tell us about how attitudes to climate change differ between generations – and what these differences mean. There have been a number of polls and surveys on this subject in the US and Europe, and these confirmed the general assumption that more members of generation Z (1997-2012) and millennials (1981-96) believe action to mitigate climate change should be a top priority than members of generation X (1965-80) and Boomers I & II (1946-64).

Aleksandra Conevska

Aleksandra is a PhD student in the department of government and a former consultant with the World Bank. She is researching the political economy of climate change, which involves topics such as attitudes to the environment among young people, the relationship between environmental disasters and politics, the losers in the decarbonisation process, and when and how societies adapt to climate change.

This is based on their greater emotional involvement, since

“beginning life in a world that appears to be collapsing is a highly emotional and existential experience”

as Aleksandra put it. A more unexpected result is that recent generations ascribe blame to governments and corporations, rather than the behaviour of themselves or their peers, at a significantly higher rate than their forebears. This can then lead to a belief that one should join a group such as Extinction Rebellion to keep the issue high on the political and media agendas. It can also lead to a belief that protest is futile, since the problem is wired into the structure of economy and society, and only extreme social change can lead to meaningful results – but that this is effectively impossible given the present political system. They belong to the class of the “climate paralysed”.

In both cases, the recent gens report lower levels of individual action, such as forgoing red meat or using public transport.

“What’s the incentive to make a lifestyle change if it’s never going to be sufficient?”

One effect of these different interprestations is that the generation gap that Boomers used to complain about is still with us, and is making it hard to build the kind of intergenerational understanding that is needed for general social mobilisation, not least in the environmental movement itself. Young people want more extreme transformational change; their elders respond that the best is the enemy of the good, and even if problems can’t be solved, things can always be improved.

Aleksandra’s final point was that there is a need to “engage and empower youth on multiple dimensions of climate action, public and personal, while still asking that other actors bear the brunt of responsibility”, since systemic transformation is indeed crucial.

“The hope is that the kind of open dialogue we’re having here can begin to address these frictions.”

THE INTERSECTIONAL APPROACH

Naomi cut her campaigning teeth at Dream Corps, an NGO begun by prominent lawyer and commentator Anthony “Van” Jones to lobby for criminal justice reform, and also to give black people a voice in the environmental movement. The point here is that sustainability and climate change have not been seen as “black” issues, and this made it difficult to recruit capable and articulate advocates like Naomi.

Naomi Davy

Naomi grew up in Washington, DC, where she naturally developed an interest in politics and law, and became a Harvard social sciences undergraduate with a focus on environment and justice. She is particularly interested on how the environment affects minority communities and she hopes to one day be an environmental lawyer. When she’s not in the classroom you can find her playing basketball or writing for the college law review.

“For a long time, green activism wasn’t attractive to people of colour and young people who’ve historically been excluded from the climate conversation.” This means that those in poorer communities who were less insulated from the effects of global warming tended to find that the debate was taking place between wealthier and whiter people who didn’t necessarily understand what was at stake for their communities.

So, Naomi’s decision to join the movement and becoming a visible, audible participant naturally encourages the accurate assumption that black people belong in it, and the movement as a whole gains a better grasp of its subject.

THE INTERSECTIONAL APPROACH

Naomi’s approach to climate change is, as she says, “intersectional” – meaning that

it looks at how unequal vulnerability to climate interacts with inequalities of wealth and racial esteem,

which in turn points to wider economic and social structures that permit pollution just as they perpetuate poverty and racial discrimination. Climate change, in other words, is about more than just the weather. Poor housing offers less shelter, low paying jobs restrict agency, and poor communities may be located in “majority-minority” cities such as Flint or Baltimore that are afflicted by environmental and social degradation, air pollution, unsafe water, and lack of access to the economic opportunities and public goods that wealthier communities take for granted.

As Naomi says “There is a disproportionate burden on them.

It is a lot harder for those communities to mobilise and so have their voices heard because they don’t have the political power to protect themselves.

“This make climate change the most important issue to be working on today, and it has given us the opportunity to completely rethink our social structures and political processes. What barriers have we put in place that make it harder to make these structural changes?”

The result, she continues, is that young people are switching the climate conversation to make it less one dimensional. Energy efficient housing is usually good housing, so how about providing grants that can improve carbon footprints and living conditions at the same time? The same goes for action to ensure everyone has clean air and water.

LOTS OF WORK, NO JOBS

The third speaker was Clea Schumer, a Harvard alumnus who now works for an NGO in Washington, researching policies to improve the natural and built environments. But this job was found only after a long and laborious search – and it was this that Clea came to talk about.

“I spent a lot of time learning about the climate crisis and advocating for change in my own community, and after I graduated I was eager to put my knowledge and passion into practice in the climate policy realm. But this turned out to be a little more of a challenge than I’d been anticipating.” The system is set up to feed Harvard graduates into sectors such as finance and management consulting, and here the jobs stretch as far as the eye can see.

In the climate realm, by contrast, entry-level jobs are sparse, and tend to ask for up to five years’ experience, thereby confronting the candidate with a well known Catch-22.

Clea Schumer

Clea is a research analyst on the climate and economics team at the World Resources Institute, where she works to help countries formulate policy on greenhouse gas emissions. Prior to joining the institute, Clea completed a degree in environmental science and public policy (focusing on climate change economics). During her undergraduate education, Clea worked at the Harvard Office for Sustainability and held internships at the California Energy Commission and the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group.

Clea also noticed that recruitment was often carried out in informal way, which made it hard to work out how to be noticed by anything other than a CV-processing algorithm. Whereas her fellow students who entered established fields could meet recruiters and find positions a year before they graduated, climate jobs popped up at random intervals when vacancies happen to arise or funding was found. And as she was later to discover fro herself, these typically drew 500 or more applications within hours of being posted.

What this means is that even the ablest jobseekers, with the best available educations, face a lengthy period of unemployment before catching – or failing to catch – a break. It took Clea a year to find her job as a research analyst with the Wealth Resources Institute, where she works on projects that help countries meet their obligations under the Paris Agreement.

EVEN THE ABLEST JOBSEEKERS, WITH THE BEST AVAILABLE EDUCATIONS, FACE A LENGTHY PERIOD OF UNEMPLOYMENT BEFORE CATCHING – OR FAILING TO CATCH – A BREAK

This cleavage between education and employment is another example of those structural problems that out speakers talked about. Clearly, as Dustin acknowledged, universities have a role in helping students find posts as research assistants or internships in environmental NGOs. Although, from his perspective, there is actually a dearth of researchers working in the climate area. “In political science,” he says, “we have very few PhD students who are doing anything related to climate. For this reason,

the Weatherhead Center is founding the “climate pipeline” programme to try to get younger scholars into the network, and match them up with senior scholars to propel their careers forward.

Questions and answers

The presentations were followed by questions from the Scotia Group members, commenced by President Carlos Salinas de Gotari, the former head of state of Mexico, who asked the panellists what they would demand from political parties that said they were committed to the environment but failed to deliver.

For Naomi, vested interests have more say in political decisions than the people in whose name they are taken, since they have more money for lobbyists, advertising and donations. “When talking about the opposition to rethinking some of the structures in our society, especially political structures that stand in the way of more radical action, I do think about the party system and how, in this country, there are incentives beyond the will of the majority. Most young people want to see a clean future for all of us, but oil companies and certain food systems control politics more than people, and this is a barrier to reform in climate, education, healthcare and lot of things that people want to change.

So the question is: how can we change our political system?”

“Structural issue”: the American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009 was defeated by the mere threat of a Senate filibuster | © US Senate Historical Office

Aleksandra added to Naomi’s argument by pointing out that many youths favour reforms that might make the structural changes required to tackle climate change. She gave the example of the Canadian Liberal Party, which campaigned on a platform that included reform of the first-past-the-post system, but did little to carry it out when elected using that very process. Her conclusion was that we have to think outside the party system, to companies and NGOs. “On a programme that Dustin organised this summer, we heard a talk by the head of management consultant McKinsey, who said young people were “not okay with not thinking about the social component of their work – so they’re taking it to their employers, outside of any public political process”.

Next, Victoria Preston, an iPlatform board member, asked Naomi to respond to Clea’s remarks about the difficulties encountered by student who want to enter the climate field. For Naomi, the largest issue for black and minority students is that sense of this not being “their” issue. Which is why the sector particularly needs minorities, since those workers in effect do two jobs, as researchers or activists, and as recruiters.

CLIMATE IS EVERYONE’S ISSUE

Scotia Group Fellow, Alex Wieler added here that

many climate positions are voluntary and seem disconnected from the substantive policy discussion. This was very much Clea’s experience.

She commented: “While I commend people who do this in their spare time, I acknowledge that people who want to work in this field deserve the opportunity to do it full-time with pay. We need more internships through universities, because they have funding and want to provide students for external organisations that may lack resources.

She added that students have already shown what they can do in a voluntary capacity, since the Divest Harvard movement succeeded, after a year of protests and strikes, in pushing the university to end its financial involvement in fossil fuels. Given adequate funding, much more may be possible.

The next question was from Howard Covington, chair of the Alan Turing Institute, who asked

why there were not large-scale protests over the failure of politicians to take action on climate?

To this Aleksandra argued that there was an awareness that academe isn’t where the action is happening. Divest Harvard had a massive success, but many other students took the view that they were better off putting their efforts into getting the grades they needed in the hopes of one day achieving a position of power.

In effect, changing the system from within – although experience has shown that the reverse is more likely …

Theodore Gilman, the executive director of the Weatherhead Center, wanted to know how young people (and everyone else) could work to change the system from within.

We all know that “business as usual” emissions from industry and agriculture have to change, so are the jobs available in the finance and consulting space for young people who want to tackle the problem?

Clea’s response was that the kind of economy-wide transformation that is required will inevitably throw up jobs in the private sector. However, we should not be naïve about what this experience is like in practice. As she put it: “A challenge that a lot of my friends seems to face is that

they take these jobs in finance or management consulting and don’t have a lot of ownership or leeway on what they work on.

Some of them are working for oil and gas companies, which is not what they want to be doing at all. At the same time, we’ll need consultants to advise governments and companies on how to do their operations better …” Finally, Professor Dahlan highlighted the important, but contentious issue, of green energy investment in Africa.

He asked Naomi whether this tension reflected a fundamental problem in relation to “saving lives in Africa” and how this relates to issues in US discourse, including Black Lives Matter.

To this Naomi identified two changes we should make in how we think about the subject.

Firstly, in the developing world, the problems caused by industrial growth are negligible compared with the problems caused by its absence.

Secondly, developing countries are at least able to take advantage of the “leapfrog” effect: that is,

the ability miss out earlier stages in technological development and fast forward to the latest versions.

Here, technology transfer from developed countries is called for, and in some cases is under way – for example the International Solar Alliance, which aims to provide a trillion dollars in funding over the next decade to develop regional grids in tropical countries.

THE WINNER

All the presentations were excellent and commended for their concise innovation and substantive policy content. The results were very close but in the end,

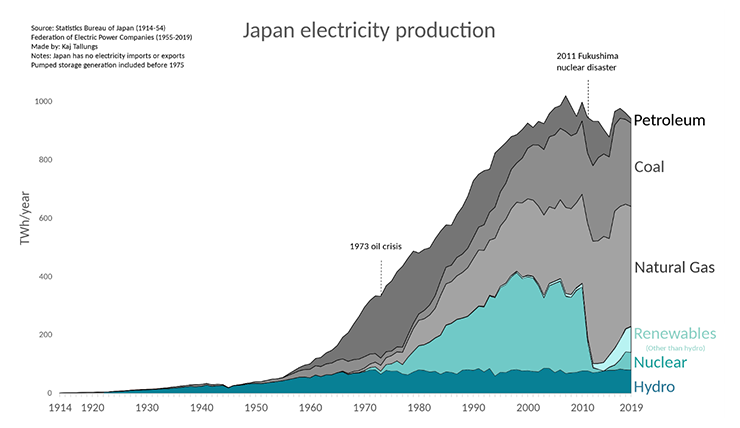

Cluster 3B with the policy proposal on Japan-Australia green hydrogen partnership won.

The prize consists of a scholarship for an online course run by either Harvard University or University of Oxford to develop their career in furthering policy development and climate action.