The struggle against climate change: Can Britain find a leading role?

The fourth dialogue of the Scotia Group was held on 21 July

a little over a fortnight before the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published the first instalment of its Sixth Assessment Report, Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, and a little less than 30 years after the UN Conference on Environment and Development produced the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, and the Framework Convention on Climate Change. This last is, of course, the document that is amended and extended by the annual COPs (conferences of the parties).

The subject the Scotia Group’s experts met to consider was how the UK, as host to COP26, could demonstrate a capacity for global leadership. Before moving onto what was said on that subject, however, we should pause and ask ourselves what has been achieved by the previous 25 COPs. This question was considered by Professor James Dallas, Executive Director of the Energy Law Institute at St Mary University of London, which jointly hosted the meeting with the Alan Turing Institute. His introductory remarks took the form of a brief yet devastating history of coordinated climate action. A generation has passed, he said, since the signatories to the Declaration and the Convention met at the Rio Earth Summit and established the consensus view that climate change was occurring, was the result of human activity, and could be solved only by concerted action by all states.

The Rio Earth Summit aimed to balance growth and environmental protection | UN /Michos Tzovaras License link

“Since then, the population of the world has increased by 2.4 billion people, the cumulative emissions of carbon dioxide, which reached 860 million tonnes in the 240 years between the start of the industrial revolution and the 1992 Earth Summit, have doubled in less than 30 years, and the the parties to the Convention have … yet to agree a voting procedure.

“We are shuffling towards the abyss, and as we go, we are nudging with us the fora and flora that we share this Earth with.”

A tectonic shift?

James did not speculate on the reasons for this pitiful result, but one possibility is that the signatories were unwilling to take any concrete steps that might retard their economic growth.

The Rio Declaration for example, was filled with assertions of the right of states to exploit resources and develop sustainably within an “open international economic system that would lead to economic growth”.

The question of how to identify unsustainable growth was left conveniently undefined.

The 1997 Kyoto Protocol followed this recognition by setting out the “assigned amounts” of greenhouse gases that each signatory could emit. The targets were modest enough, and ignored aviation and shipping, but the US repudiated them in 2001, China and India were left out, and the remainder of the developed countries met their targets only with the help of carbon credits and the 2008 financial crash.

The result of all this can be read in the words of Climate Change 2021.

“Human influence has likely increased the chance of compound extreme events since the 1950s. This includes:

increases in the frequency of concurrent heatwaves”

Northwest America’s “heat dome” | European Space Agency License link

“… droughts on the global scale”

Australian pastureland | VirtualSteve |CC BY-SA 3.0 License link

“… fire weather in some regions of all inhabited continents”

California wildfires light the horizon | Public Domain License link

“… and compound flooding in some locations.”

Klaus Bärwinkel License link

But has that mood of passive concern now changed? James thinks it has.

“A tectonic shift has taken place in the past seven years.

Climate change is impacting every aspect of what we at the Energy Law Institute teach in this sector, from the nature of projects to regulators, lenders, investors and governments. The courts of the world are awash with challenges to governments in action and corporate failings, and international oil companies are facing the need for rapid change.”

The British case

One theme of all Scotia Group meetings so far has been the importance of economic constraints on climate action. Governments do not get elected by promising to boost unemployment, and businesses wants to make money come hail or high water. So, the words of Howard Covington, the inaugural chair of the Alan Turing Institute, and the second of our introductory speakers, offered some encouragement, since he agreed that a change has finally come.

“We seem to have reached a point of inflection,” he said. “The climate problem is recognised, clean tech is as cheap as fossil tech and getting cheaper and governments have promised huge reduction in emissions.”

But what has the UK done to break the presumed inverse relationship between climate action and economic growth? Well, quite a lot, actually,

since the UK’s total greenhouse gas emissions were 49% lower in 2020 than they were in 1990.

Some of this was fortuitous – a shift to gas in the nineties that wasn’t undertaken purely for environmental reasons, the 2008 crash and the advent of the Covid pandemic – but some of it was the result of the 2008 Climate Change Act and a rapid development of offshore wind power.

Lord Adair Turner

The first of the conference’s main speakers was well placed to unpack and analyse what the UK got right, and what other countries can learn from its approach, because he was present at the birth of the country’s climate change strategy.

Lord Adair Turner

Lord Adair Turner was the chair of the Financial Services Authority until its abolition in March 2013. He is a former chairman of the Pensions Commission and the Committee on Climate Change, as well as a former director-general of the Confederation of British Industry.

CBI | License link

The UK Climate Change Committee is an independent, statutory body of experts established by the 2008 act. Lord Adair Turner was its chair during the first five years of its existence, and saw the effect that it had on government and industry.

TARGET

The most important point, he said, was to establish forceful policies. If industry is convinced the government means what it says it means, and is going to continue to mean it for the next 50 years, then it will naturally, rationally, fall into line. So, if a steel maker is considering whether to switch to hydrogen and produce a more expensive product, it will go ahead only if it believes the government will compel all its competitors to do the same. The same is true of the government itself. The vast, rambling confederacy of fiefdoms that makes it up can be marshalled if, and only if, all are convinced that they have no choice but to comply with an overriding policy objective.

The creation of this perception was a large part of the Climate Change Committee’s job. Like that other snarling watchdog, the National Audit Office, it is not answerable to government, but to parliament. This means that it can hold the executive to account without worrying about any embarrassment it may cause.

Another important means of encouraging faith in climate change policy, Lord Turner argued, is predictability and transparency. In 2019 the government set a target of reaching carbon neutrality by 2050. This period is divided into five-year “budgets” that state how much greenhouse gas is going to be emitted, beginning in the period 2008-12 and now stretching to 2035. Parliament agrees three of these in advance, so all large-scale emitters know what will be allowed over a 15-year period, and the government knows that it will be subject to legal challenges and judicial reviews if it fails to keep to the stated limits. This then forms what Lord Turner called a “forcing mechanism” – the government knows that it has to take action or else it will break the law.

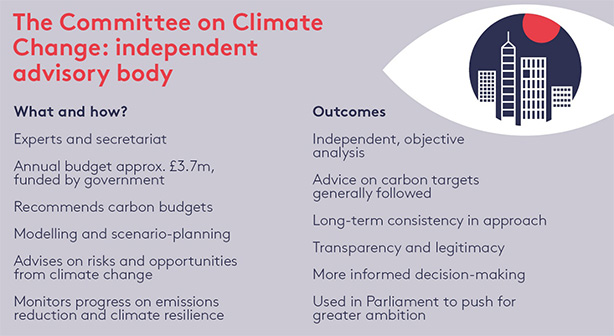

A Climate Change Committee crib sheet | London School of Economics

Thirdly, there is the Climate Change Committee itself. “It’s not a huge body – about 25 or 30 people – but it produces high-quality analysis of what it is we need to do to set and meet the carbon budgets.” This then sits on the shoulder of government and continually reminds it what it has to do to meet its carbon budgets, and how it can do it.

For example, it employs stock-flow consistent models to determine the answers to question such as how quickly it will be possible to decarbonise road transport once a certain percentage of electric vehicles are sold a year.

“It is always looking for an economically feasible path from A to B within an non-negotiable commitment to get to net zero by 2050, at a pace that is compliant with our national determined contribution under the Paris Climate Agreement.”

Finally, how successful has the committee, and the government, been in keeping the UK to its carbon budgets? Here the picture is mixed. “We have met the first three budgets, but unless we tighten policy considerably, we will not meet future ones,” Lord Turner noted.

“The sixth carbon budget requires that by 2035 we achieve a reduction of 78% below the 1990 level.

That is a stretching target, and will require more action by government than it has taken so far.”

The UK exceeded its target for the 2020 carbon budget, but is on course

to miss 2050 by a wide margin. Source: Climate Action Tracker

For some sectors, we are on the right trajectory. The UK will decarbonise electricity generation sector by 2035, assuming the government meets its commitment to have 40GW of turbines in the North Sea by 2030. In road transport, the government will ban the sale of passenger cars powered solely by internal combustion by 2030 – a move that Lord Turner said

“would not have happened without the forcing mechanism of the committee”.

Other areas present more of a challenge: a switch from gas boilers to heating based on hydrogen or electric heat pumps will cost a lot of money, and government at present has no sense of whether it is going to subsidise the transition or force individual to fund it from their own pockets. More will be known when the government publishes its Heat and Buildings Strategy.

SPEAKING OF FORCING MECHANISMS…

The government knows it will be subject to legal action if it busts its carbon budgets … which raises the question of how effective that action is likely to be in practice. Well, the UK is a lawful state, and so governments will comply with the decisions of domestic courts if they can, or face accusations that they have gone rogue.

In fact, the existence of an external authority allows politicians to play a “two-level game” – playing off the courts against factions within the government that do not wish to back a “stretching” policy, particularly when it involves difficult decisions, such as replacing 27 million gas boilers.

And it seems that the courts are willing to take up that role. Sir William Blair, who addressed the meeting in his capacity as professor of Financial Law and Ethics at Queen Mary, gave a situation report on how the legal climate has changed over the past few years.

Sir William Blair QC

Sir William Blair QC

Sir William Blair QC has advised, argued, judged and arbitrated in many disputes around the world, particularly in the financial field. He iwas a judge in the London High Court in 2008 and in 2016 was named Judge in Charge of the Commercial Court.

In the academic field, he has been a visiting professor of law at the London School of Economics, Peking University Law School, East China University of Politics and Law and the University of Hong Kong. He retired as a High Court Judge in 2017 to take up a position as Professor of Financial Law and Ethics at the Centre for Commercial Law Studies, Queen Mary University of London.

We are, he said, observing the beginning of a wave of litigation related to climate change, both in civil code and common law jurisdictions. He quoted from a recent paper from the London School of Economics that assessed the global trend in climate litigation.

This detected a rise in the number of “strategic” actions – that is, those brought by activists hoping to compel governments to set tougher targets or reverse particular decision. Up until the end of May, there were some 1,848 continuing or concluded cases, three quarters of which took place in the US. Furthermore, around 121 new case have been filed in the past year, which Sir William said sounded like a big number, but actually wasn’t. Nevertheless, the scope for more filings is obvious, particularly if it seems the courts are receptive to the kinds of arguments that activists put forward.

And, as Sir David Edward suggested in his talk to the third Scotia conference, there have been a number of important decisions. Both the French and German governments have this year suffered spectacular defeats in their courts, and will have to amend their laws as a result.

Meanwhile, an Australian court’s decision in Sharma v Minister for the Environment, also discussed in the last dialogue, established the important principle that judges will consider the interests of future litigants – that is those who stand to lose most from climate degradation. This will be further tested in a case before the Federal Court in Melbourne in which a 23-year-old law student is suing the Office of Financial Management and the Treasury on the grounds that are deceiving investors by not disclosing climate change risks in exchange-traded debt. “A big ask of a court,” Sir William thinks, but not impossible when you “stand back and look at the big picture”.

All of those cases have developed public environmental law. The real landmark, however, was the Milieudefensie judgment of the Dutch constitutional court, which for the first time ordered a private company – Royal Dutch Shell Group – to curb its own carbon emissions and those of its customers.

Environmental group Milieudefensie (Friends of the Earth) | Marten van Dijl/Milieudefensie

Some of these cases are subject to appeal, so we do not yet have the definitive picture. However, the indications are that this may not be an area where the UK is taking a lead: Sir William referenced the decision of the Supreme Court in January to overturn a block on the construction of a third runway at Heathrow Airport.

He explained this by the fact that the common law system in England and Wales “does not have same overarching procedures as Germany and France”. Nevertheless, passive concern about climate change is now shifting to active alarm, as more and more influential people come to realise that Planet Earth might be a more dangerous place for them than they had been led to believe, so we should expect that more precedents will be set, which in turn will stimulate more and more litigation.

THE GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

If those present at the dialogue took heart from what Lord Turner and Sir William Blair had to say, the remarks of Lord David Howell, the dialogue’s third speaker, came as something of an ice bucket down the back of the neck.

Lord David Howell

Lord David Howell, an economist by training, has had a long career in journalism, parliament and government.

Lord David Howell

Lord David Howell was Margaret Thatcher’s first energy minister and an adviser to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office on energy and resource security. He has also been president of the British Institute of Energy Economics and chair of the Windsor Energy Group. Among his published work is Out of the Energy Labyrinth.

Roger Harris License link

“We can’t be left in any doubt that in the UK, we’re doing rather well,” Sir David began, gently enough. “All political parties in successive governments accept the case for fighting climate change and have agreed the targets” – even though, as Lord Turner noted, we have yet to take the truly painful decisions.

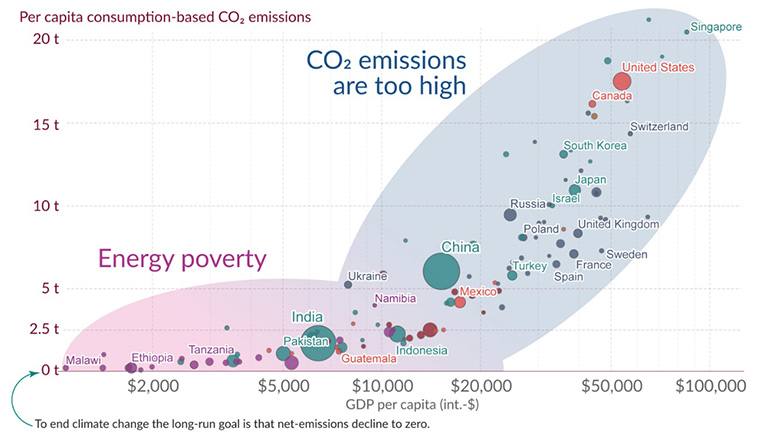

It is, alas, a fact that no matter how well the UK performs, it is responsible for slightly less than 1% of global emission. “Look at global picture and what do you see?” he went on. “Firstly, emission rising rapidly after the pandemic – a rise that is expected to continue throughout the 2020s. The Paris Agreement asked for a 7.6% reduction every year to limit the rise in average global temperature to 1.5°C.

We’re miles away from that and moving further, and this is very, very serious.”

The reason for this failure to meet the Paris target is that Asia, Africa and Latin America still have to develop their economies to Western levels, and although they are presently massive carbon emitters, in historical terms their contribution to cumulative greenhouse gases is comparatively small. China, for example, had 1,040 gigawatts of coal-fired power stations in 2019 – around 16 times greater than the entire installed capacity of the UK – but its contribution to total carbon since 1751 is about half that of the US.

Source: Our World in Data License link

What’s more, although Milieudefensie was a wake-up call for the international oil companies, the fact remains that about half of our hydrocarbons come from national oil companies, and these would appear to be beyond the jurisdiction of Western courts.

So, the “gloomy reality” is that whatever happens in the UK may be virtuous, splendid and admirable, but it is also futile.

IT MIGHT BE OBJECTED THAT EVEN IF THE UK CANNOT MAKE A SIGNIFICANT CONTRIBUTION IN TONNES OF CARBON EMITTED, IT STILL SHOWS OTHER COUNTRIES THE WAY THEY CAN TAKE ACTION OF THEIR OWN, AND PERHAPS EVEN INSPIRES THEM TO EMULATE ITS EXAMPLE.

This point runs up against the same impulse that muted the Rio Earth Declaration, albeit with rather more justification in gross domestic misery. “I travel the world to conferences and I have to tell you, I haven’t heard much talk about examples. I just don’t hear it. I hear instead that there are 2.8 billion people with no access to grid electricity. I hear that half the world – 3.5 billion people – does not have access to reliable power.

China has a terawatt of coal-fired capacity | Tobixen/GNU

“The task for many countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America, their entire momentum, is to get the cheapest electricity to their people in the shortest possible time, and they’re not going to stop unless a lot of money comes along. That is the reality. If we’re going to delay delivering power to people who need it, they will want funds from the countries that caused all this in first place.” How much money? Well, whatever the notional sum might be, it will probably have 11 noughts after it.

SPEAKING OF CHINA

The final speaker at the conference was somewhat off the topic of the UK’s role in leading, or not, the global effort to curb carbon, but in light of Sir William and Sir David’s remarks, he was very much part of the dialogue.

This was Dimitri de Boer, the Chief Representative of ClientEarth in China, and what he had to say presented the delegates with another illuminating perspective.

Dimitri de Boer

Sir William made the point that legal systems only can play a part in holding governments to account if they recognise the rule of law. And it is generally understood among Western commentators that this is a questionable proposition when it comes to China’s strange system of government, in which the Communist party seems to dominate legal and administrative institutions.

Dimitri de Boer

Dimitri de Boer is based in Beijing, and heads ClientEarth’s China office. He is one of China’s most prominent environmental cooperation experts. Between 2010 and 2015, he led the EU–China Environmental Governance Programme, which promoted access to information, public participation and access to justice. When the EU Programme came to a successful close, Dimitri joined ClientEarth and started its China office. He quickly built relations and cooperation activities with China’s Supreme People’s Court and Ministry of Environmental Protection.

Chongqiong seen through a veil of smog | (Photoholgic / Unsplash)

Dimitri’s talk presented a radically different picture.

It is certainly true that China, with its terawatt of coal-fuelled power stations, is responsible for about a third of global emissions. And it is true that many OECD countries are reducing their emission while China’s will continue to rise for the next 10 years. However, it is also true that China is consciously using its domestic court system to allow civil society to challenge the state.

Back in 2014, James Thornton, the founder of ClientEarth, visited China to attend a meeting to discuss environmental public interest law. Present were members of the Supreme People’s Court, the Ministry of the Environment and legislators from the National People’s Congress. “At that time,” Dimitri said, “there was a lot of hope that through public information disclosure and opening courts to civil society and to public interest prosecutors, it would establish a much more modern environmental governance system in China, rather than relying on top-down directives, since everyone was quite clear that there were limitations to what can be achieved by that.”

After he gave his talk, one of the People’s Court judges approached James in private and asked him to set up an office for ClientEarth in China – which is what happened – and over the past couple of years, environment courts and tribunals have been established at all levels of the Chinese judicial system, and prosecutors specialised in public interest environment law have been formed around the country.

In 2020 those prosecutors have brought more than 80,000 cases. One of largest – worth more than £3bn – involved the rolling up of an organised crime syndicate that, among many other things, carried out illegal sand excavation.

“The biggest punch they took was an order that they remediate all the damage they’d caused to the environment.”

Furthermore, it seems the Chinese central government is using the courts as its own forcing mechanism, but here the aim is to compel powerful municipal governments to adopt better environmental practices. Of course, there are also the top-down decrees – the most important of which, President Xi Jinping’s pledge to go carbon neutral by 2060, led to widespread public discussion among officials and researchers about how that could possibly be achieved.

Alongside this surge in judicial activism, the government appears to be moving to ban the funding of coal-fired power stations on projects funded under the Belt and Road Initiative – partly as a result of ClientEarth lobbying. No new coal projects were approved in 2020, most that were proposed earlier have been shelved, and this year Chinese financial institutions have begun pulling out of large BRI coal plants. “Just last Friday, a government policy was introduced that sets green standard and green bottom lines for China’s overseas investments.”

Source: Region.svg License link

All of which is encouraging, but it does not alter Sir David’s point that China is presently doing more than any other nation to ensure that the 1.5°C target will not be met.

Coal power may be not funded under the BRI, or by the Beijing-based Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, but last year 53 gigawatts of new coal was approved anyway, and China’s emissions of greenhouse gases are running about 50% above pre-Covid levels,

which means that the leeway that China set itself for increasing emissions between now and 2025 has already used up.

The Climate Majlis

The closed-door majlis session was an opportunity for expert discussion and open questioning among many former and current leaders in energy politics, as well as international climate change lawyers. It was moderated by Professor Dr Malik Dahlan, the Scotia Group’s founder, and Howard Covington. Professor Dahlan began by reiterating the aim of Scotia Group: to promote the kind of strong policy and the culture of open challenge that Lord Turner said was essential for making forcing mechanisms work.

The group now partners with eight universities and three policy research bodies, and will soon be able to draw on the expertise of almost 100 leading doers and thinkers in the worlds of business, academia and governance.

Nevertheless, we are talking about nothing less than a shift of geological epochs – from the Holocene to the Anthropocene, and the facts and numbers are daunting. If climate change is to be tackled within the framework of liberal polities, we have to find a way to “mainstream” the challenge despite the layers and layers of governance.

“What we’re talking about is a global ordering problem, so strong policy is the only way forward. I find it troublesome that the investment intensity required has not been established in the way we need to – as much as $35 trillion over nine years.”

Our diplomacy also has to be more forceful, particularly when it comes to national oil companies. We need an energy transition diplomacy roadmap, and this will take at least 18 months to set out, but will this even be tabled at COP26?

WE NEED AN ENERGY TRANSITION

DIPLOMACY ROADMAP WHEN IT COMES TO

NATIONAL OIL COMPANIES

The bullet points

- One starting point for thinking about COP26 is that clean tech has been developed, so an energy transition is technically feasible. Governments are promising to put that tech to work – so how do we use the courts and civil society to keep them honest? In particular, what will happen when there are hard political choices to be made? In the UK, a recent report by the World Wildlife Fund said new green policies in the UK’s March 2021 Budget added up 0.01% of GDP, whereas the Climate Change Committee had said 1% of GDP must be spent every year to ensure climate targets are met.

- The UK has plucked much of the low-hanging fruit, particularly in the case of electricity, where the government hasn’t had to get into people’s lives, In the next few years, governments at national and subnational levels are going to have to engage with citizens much more, because the next steps will be done with their cooperation and forbearance. One problem may be that the present UK government tends to prioritise slogans over the hard work of engaging with stakeholders. There is a policy gap between ambition and practicalities, as investment mindset and the system thinking that could synthesise economic and social goals. In short, it is too early for the UK to claim global leadership in the energy transition process.

- In the case of the US, there is an obvious lack of industrial policy at the federal level, but many things are happening at the state level – it’s just that, in general, we don’t know what they are. We need to compile a catalogue of what those states are doing before we can get a sense of where America is going. As for the global picture, everything depends on two issues: coal and China.

- The Scotia Group has the opportunity to speak to government, business and civil society, but it should also reflect on its connections with UN. This body may not possess forcing mechanisms, and UN civil servants take an oath to be outside the influence of any national government, but they see Scotia as a way to raise subjects they are concerned about.

- The oil producing companies, the Gulf states and the wider Middle East face a particularly harsh variant of climate change, since water resources are under strain and cities such as Dubai are at risk of disastrous flooding. They will be able to meet the challenge only if they follow a two-pronged strategy: fighting corruption and waste among elites and introducing economic measures to rebalance wealth inequality. If you are asking people to make sacrifices, they must be given more voice in determining their future. If they do not make those concessions, elites will face increasing insecurity, both domestically and regionally. One way or another, they are going to be forced to live in a new world.

- Demand for fossil fuel is going to continue at a high level even after we reach peak oil. The International Energy Agency has said investment in new oil, gas and coal should stop – but that not going to happen. A new way of deploying resources is required. Europe spends its money on achieving local net zero, despite the difficulty and the expense and the likely need to impose high energy bills on poor households, convert domestic boilers, eat less meat, take fewer holidays and transform farming. Would it not make more sense to spend that money on helping China, Africa, the Indian subcontinent and Latin America adapt their production and consumption systems? If we want to cut global carbon, that is where we would achieve best value for money.

- Rather than spending money in Europe on capturing carbon, should the emphasis rather be on adapting our built environment to deal with harsher weather and more frequent floods? It is inevitable that climate change will continue for some time, so we can be confident that there are going to be increasingly frequent disasters.

- There is widespread doubt as to whether the COP system is sufficiently coherent and robust to coordinate global environment policy. Passing resolutions and revising the Charter is not gong to ensure that progress will happen. In addition to the COP, we need new multilateral institutions with the scale and vision of the Bretton Woods bodies. After all, what is under discussion is nothing less than the reform of the entire world financial system.

- There are some gaps in national frameworks for climate change laws. We don’t only need long-term targets, we also need interim targets, clarity as to how they are to be achieved, and by whom. At the moment, this is generally not clear at all. It is also essential to have one government department in charge of, and accountable for, climate policy. We also need to prepare for adaptation as well as mitigation. Policy needs to be underpinned by strong emissions pricing with clear floors and limited allowances – at present, many carbon trading schemes are only partially functional because of flaws in their governance structures. We should also avoid emissions pricing without the phasing out of subsidies on fossil fuel and freezes on fuel price rises. They money saved should be used to finance policy, and also to address the problem of global as well as national income inequalities that will arise as a result of the transition to net zero.

- We should increase the disclosure requirements imposed on companies and financial institutions in order to made transparent their exposure to climate change risk and their contributions to climate change growth. Alongside this, we require stronger regulators with higher capability and capacity and larger budgets. There are laws in place to enforce disclosure requirements on companies, but regulators typically fail to use them. Without that, the private sector will not move in any meaningful way towards net zero.

- Most of the chemistry of batteries is built on nickel and this is a metal that found beneath the soil of rainforests. Plans are afoot to look for nickel on the sea floor, which poses an obvious threat to marine ecosystems. In moving to battery-powered cars and grids, we must make sure that we limit the effect on our environment. We should focus on energy that does not rely on damaging mineral extraction: green hydrogen, and graphine or aluminium-based batteries.

- We need to think about the level at which decisions are taken. At the moment, most are made by national governments with little public participation. We should ask ourselves, from a governance perspective, how roles and responsibilities could be apportioned so that decisions are made at the lowest levels possible and with the fullest possible public participation. That would be a way to induce cognitive change and get people to engage with the transition. It would also be a way for them to understand the benefits as well as the costs

- The UN Framework Convention requires reform. Rather than waiting for the system to fall apart, we should accept that it is not working. We should consider moving to smaller regional groupings that could be much more effective.

- To get oil companies on board with climate change action, we have to show them a roadmap that leads them to believe that their share of the global energy market will remain the same. And this also applies to energy workers at a domestic level: they have to believe that they will keep their salaries, otherwise we will have a democratic problem.