Institutional action

The third Scotia group dialogue was held online in partnership with St Andrews University

The purpose of the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference is the same as those that came before: to allow states that are parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change to review and amend that Convention. So, the Conference of the Parties is the supreme decision-making body of the Convention. In effect, it is both a legislature and an executive, and what it will ultimately produce will be an instrument of international law.

Participants at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference.

©Roberto Stuckert Filho | No changes were made. License link

As with any legislative process, there is a downstream and an upstream element: a period of research, consultation and lobbying before the COP, followed by a period of implementation once the revised text of the Convention has been agreed.

In the Scotia Group’s May dialogue, the focus was on the downstream segment. It discussed (among other things) the building of sub-national coalitions that could inform and influence policy-making and complement the actions of national governments – or even bypass them if they fail to take effective action. In this meeting, the emphasis was on the upstream part: how to formulate planning and policy that has a chance of curbing global warming before it reaches the point of no return.

But since the Convention is in essence an agreement between governments, it cannot be enforced directly by a national court

The COP may function as a kind of international law-making body, but the only way its decisions can be judicially enforced is by domestic legal systems. This has the potential to give courts a leading role in the policy formulation process. They are the only bodies that are able to hold governments to account, and – crucially – they are accessible to climate change activists. This means that they could, in theory, act as a kind of driveshaft connecting the people with the machinery of government. But how willing are courts to play this role?

This was the question tackled by the first speaker.

National courts

Sir David Edward gave the dialogue a series of case histories that illustrate how legal systems in Europe and Australia have dealt with recent environmental challenges.

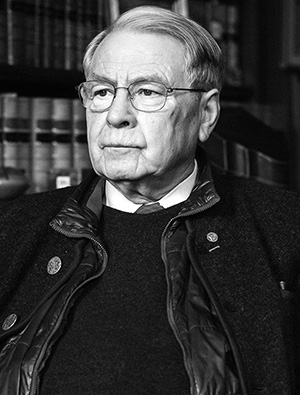

Biography

Sir David Edward

Sir David is a Scottish lawyer and academic. He became a QC in 1974 and went on to sit as a judge at the European Court of Justice. He is an honorary fellow of University College, Oxford, an honorary professor of the University of Edinburgh and Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. He is also an honorary Sheriff of Tayside, Central and Fife.

The first case illustrates the default position. It dealt with an appeal brought before the Federal Administrative Court of Switzerland in 2018 by a group called the Climate Seniors Association, which was made up by about 2,000 women over 74. Their demand was that the Swiss government protect them from heat waves by bringing forward tougher environmental legislation. Their case was dismissed on the factual grounds that older people are not in greater danger than the rest of the population.

“There may be an obligation – but you can’t enforce it. There are plenty of examples in EU law of cases like that.”

This seemed to suggest that national courts would not play much of a part in forcing states to adopt policies that responded to the scientific consensus as expressed in the Convention (and elsewhere). However, it has been followed by a number of landmark rulings that point in the opposite direction.

In 2019, the Dutch supreme court heard Urgenda Foundation v State of the Netherlands, in which an environmental group representing 900 citizens successfully sued their government on the grounds that its climate change policy was insufficiently tough. This case showed that, although courts cannot enforce the Convention directly, national constitutions can be used to enforce them indirectly.

© Urgenda | No changes were made. Source link

This was followed in May 2021 by a ruling from the Hague district court in the Milieudefensie case, in which the Shell Group was the subject of a class action brought by seven NGOs and more than 17,000 individuals. The implication here was that courts would not only deal with claims against states, but also private companies – a huge increase in their scope of action. The result was a judgment that the entire Royal Dutch Shell group had to cut emissions at least 45% by 2030 – as did customers who burned its oil and gas.

© Marten van Dijl | No changes were made. Source link

In the same month, Australia’s Federal Court issued a ruling in Sharma v Minister for the Environment, a case brought by eight Australian children on their own behalf, and as representatives for every Australian under the age of 18. They argued that a decision by Sussan Ley, the Federal Environment Minister, to approve a A$700m extension to the Vickery coal mine in New South Wales contravened her duty of care to Australia’s children as set out in the 1999 Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act. The court found that the government does indeed owe a duty of care to Australian children and had to consider their interests when making decisions.

The final case Sir David addressed was a case brought by NGOs and young people in the German Constitutional Court. This argued that the 2019 Federal Climate Protection Act violated their constitutional rights by setting carbon reduction targets too low. Here, the court ruled that the government could not limit climate obligations if that would cause unacceptable problems for future generations. It ordered that the legislature must set clear reduction targets for 2031 onwards, and must do it by the end of 2022.

The conclusion that Sir David drew from these cases, and a number of other pending in Canada, Mexico, Guyana and the UK, is that it is not enough to conclude intergovernmental agreements;

“What COP26 ought to do is open the opportunity for individuals and representative groups to take action in national courts.”

Sir Ian Boyd

The second speaker at the dialogue was Sir Ian Boyd, who is chair of the Environmental Sustainability Board at the University of St Andrews. He tackled the question of enforcement and implementation from a position of administrative pessimism. So, many governments have now declared that they will be net zero by a particular date, and some (Scotland and the UK included) have passed legislation and set up oversight and planning bodies to ensure they meet it.

And yet, how confident are we that a government – even one that has been found guilty by a court – has the ability to keep its promises, no matter how much it may want to?

Biography

Sir Ian Boyd

Professor Sir Ian Boyd was Chief Scientific Adviser at the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs from September 2012 to August 2019 and is currently Professor in Biology at the University of St Andrews. His career highlights include a stint as Science Programme Director with the British Antarctic Survey, Director for the Scottish Oceans Institute and Acting Director and Chairman with the Marine Alliance for Science and Technology for Scotland.

He has received the Scientific Medal of the Zoological Society of London, and the Bruce Medal (awarded once every four years) for his research in polar science. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and the Society of Biology.

“In my experience, having worked within government, they have a kind of paralysis brought on by the sheer scale of the challenge,” he said. “Industrial sectors have transformed in the past, but rarely have they ever transformed at the rate needed to adapt to climate change, and never have they transformed in parallel, in the way that we require them to do over the next 20 to 30 years.”

If it’s true that governments are unable to effect the required changes in industry and society, it follows that the first thing they have to do is to change themselves. The problem is that, in practice, enormous force is required to overcome institutional inertia – even an external shock as violent as the 2008 global financial crisis, plunged the UK met into a decade of austerity that degraded the public realm yet did little to upgrade the machinery of government.

©Climate Action St. Andrews | No changes were made. Source link

What’s more, it is far from clear that governments’ rhetorical commitment to climate change is really reflected in policy outputs. Any political realist knows that governing is a bargaining process in which the views and interests of many internal and external groups have to be reconciled, so there is little chance of achieving the whole-of-government effort that climate change calls for.

The conclusion that Sir Ian drew from this analysis echoed the proposition put forward by Andy Kerr in the second dialogue, which is that it falls to sub-national groups to “step up” and carry out the policies that governments would develop if they were able. But whereas Andy had municipal bodies in mind, Sir Ian discussed the roles civil society and businesses can play.

The University of St Andrews has put together a strategy to reach net zero by 2035 – 15 years ahead of the UK target

©Wikipedia | No changes were made. License link

To illustrate this point, he gave the example of the University of St Andrews, which has put together a strategy to reach net zero by 2035 – 15 years ahead of the UK target (and 10 years ahead of Scotland’s). The reason for this tight schedule is that few institutions are as well placed as a university to achieve the goal, which means that their journey to net zero can act as demonstration projects for the rest of society.

Although this process is just getting started, some principles have already emerged.

One is that buy-in has to be as wide as possible, and initiatives should be simultaneously top-down and bottom up. More specifically, the university has set up an environmental sustainability board that is representative of the whole of the university.

Another is that carbon is not the whole story, nor the only target.

Care for the environment means preserving biodiversity, using resources sustainably and extending both to agriculture as well as industry.

The third consideration is delivery and planning, which involve making the business case for change at the operational level: how the university and its people buy, build and behave.

The fourth touches on the function of a university. Here the aim is to carry out research into sustainability and deliver students to the workplace with a clear picture of what the term means and how it can be achieved.

Fifthly, one university doesn’t have much weight on its own, but the whole of the educational sector does. Exemplary projects have the possibility of setting new standards and galvanising other institutions into emulating them.

Finally, the university can be considered as a social and economic organism, with more or less the same inputs and outputs as any other. Some of those inputs can be controlled: it can buy electricity from a renewable source, for example, or increase the amount of heating that comes from biomass rather than fossil fuels.

However, that is a relatively small part of the university’s footprint when compared with what it buys and builds, and how its members travel. The problem is that these are in the hands of external suppliers. It is comforting – but false – to imagine that all those suppliers will also carry out their businesses sustainably, leaving the Environmental Sustainability Board free to concentrate on changing electricity supplier: that way lies tokenism.

So, to offset this uncontrollable carbon, the university has to absorb it. “If we cannot do that we are not playing our part in getting the whole nation to net zero.” In St Andrews’ case, that means planting a forest.

Lea Wiemann

The presentations at this third dialogue followed a progression. They moved from the hyperrational realm of the legal system, to the broad but still specialised world of institutional governance, to end at community activism, where we find the passion and conviction that furnishes the law with its cases and the university with its students.

Biography

Lea Wiemann

Lea is a recent graduate of the University of St Andrews but eco-activist with 10 years’ experience of spreading the message about climate change.

What gives this form of activism its sense urgency and energy is the sense that governments are failing to tackle the problem by international agreement or domestic legislation. “We haven’t successfully addressed the issue despite holding Conference of the Parties meeting for 30 years now. And why is it that, despite the growing consensus on climate change it is not necessarily reflected in the people we vote into power or the societal changes that we need?”

Lea’s take on this was that

“we’ve become really comfortable in a hot pot”

– a reference to the frog in the saucepan, which doesn’t notice that its position is untenable until it’s too late.

So, here are two points to think about. Firstly, if you’re a frog that has become aware of the situation you’re in, it’s in your interests to participate in changing it. Use your skills, talents and social media accounts to argue for change. “I would argue that the only reason we’re seeing some real changes in the world is because of community activism,” Lea says. “It’s because of young people striking, protesting, speaking up about it.”

Secondly, Lea acknowledged that activism is difficult to keep up in the long term, and yet is a long-term activity – she’s spent 10 years building up her platform. This raises the question of how we make campaigning for sustainability sustainable. Here the key is giving people the sense that they are getting somewhere and part of that is giving activists a “voice at the table”.

©Markus Spiske | No changes were made. Source link

The dominant theme of the legal cases discussed by Sir David was the duty of care one generation owes another; Lea argues that that has to influence the way we set up our debates. Community activism needs as many channels of expression as possible, and if that expression leads to concrete results we can hope for a virtuous circle in which the more effective involvement is, the more sustainable it becomes.

And this is something that the Scotia Group has taken to heart.

a number of St Andrews’ students will be joining Lea on our newly established Scotia Fellows programme

The dialogue was audited by a number of St Andrews’ students who will be joining Lea on our newly established Scotia Fellows programme. This idea, as explained by Scotia founder Malik Dahlan, is that each of the group’s partner universities nominate five students as fellows.

“We have asked them to be patient until they listen to the dialogues and majlises. We need some time to come up with our ideas, but then we will give them the chance to have their own conversation, and we listen. They will hold their own public debate in September, with the aim of choosing which of the Scotia group’s policy proposals are ultimately presented to the Glasgow conference.”

The Majlis

The majlis was a closed-door session, moderated by Professor Dahlan. The conversation began with comments from representatives of the UN and a number of participants with business and investment expertise. A range of topics were raised, including the importance of harnessing existing knowledge in developed countries to support and facilitate equitable energy transitions in developing countries – a point that has preoccupied Scotia delegates at every meeting so far.

The major themes that then emerged from the conversation were:

- The importance of the private sector. The main argument here went as follows. In Western countries, the amount of capital available to financial markets and private businesses is immensely greater that that available to states. Climate change requires large-scale capital investment to upgrade the physical, social and digital infrastructure we all rely on. Therefore, the climate challenge will not be overcome without business.

- We know that businesses and states could combine to tackle climate change. The example set by the life science and pharmaceutical sectors in developing Covid-19 vaccines was impressive, however imperfect the coordination and distribution was in some cases. The discussion then covered ways to incentivise this investment.

- The state certainly has its role to play in pushing businesses to act, with the tax and regulatory systems providing tasty carrots and painful sticks, and the Milieudefensie case proving the possibility of courts intervening to regulate corporate behaviour.

- However, it was also pointed out that in our capitalist systems, money makes the world go round, and it was therefore essential that businesses be able to make a profit from reducing their emissions and producing the equipment we need to cut carbon. One member argued that there were substantial and realistic opportunities for the hyper-capitalist US to emerge as a leader in the transition to clean energy.

- In the special case of oil and gas companies, it was proposed that they be given two years to devise an agenda for change, and here negotiation and partnership is more effective that shaming.

- The question of intergenerational equity is undoubtedly important, however it was argued that it should not eclipse intragenerational fairness, particularly when it comes to developing countries’ struggle for resources. As the inequality in vaccine distribution has shown, the more a country needs finance, the more difficulty it has in obtaining it, and the life-saving technology it buys. As with community activism, any effective response to climate change requires support, and support requires investment at a level that makes a difference. So, we need a fundamental improvement in development finance.

©www.reddit.com | No changes were made. Source link

- Another speaker underlined the importance of investment, and also the difficulty in soliciting it in response to climate change, since all the costs have to be paid up front, and the benefits are invisible, since they are conferred by things not happening. This is a common issue in policy making and no political system has ever dealt with it particularly well.

- We should limit our expectations about COP26. It will be important for stating aspirations, setting targets and sending signals about what states consider important – but they don’t always lead to action. Consider the UN’s millennium development goals: how many have been fulfilled?

- Regarding development finance, we can be 100% sure that the money that developing states need will not be made available to them – they will get promises, but not the money. So, the main action will be national and it will be market-based (whether on the supply or demand side).

- A problem here is that the debate can be confused – these days, terms like business, markets, social justice and corporate responsibilities aare emotive and contested. We should keep the debate focused on carbon.

- Finally, the state is important because it is capable of thinking in longer terms than large public companies, who always have to consider their next quarter’s filing.